The most evictions in Ontario happen in these major cities

Published March 5, 2024 at 3:17 pm

Two years ago, Nicole Brown received a letter from her landlord offering her and her family money to vacate the Brampton apartment they had been living in for close to 10 years, leaving them anxious and distressed about having to move at a time when rental rates were skyrocketing.

“It was just an offer to give up the unit. It didn’t say we had to leave,” Brown told insauga.com, adding that she received the letter shortly after a new property management company purchased her Main Street building and began renovating units.

“It said considering the construction and changes, there was an offer to leave the building. We just couldn’t find anything affordable at the time. It was the peak of the pandemic, and units were three to four times what we were paying, with some asking for $2,500 upfront. We just couldn’t afford to move at the time.”

Fortunately for Brown, the landlord took no further action when her family rejected the offer. Still, a report released by ACORN, an anti-poverty advocacy organization that represents lower and middle-income residents across Canada, shows that more tenants are being told to vacate their units.

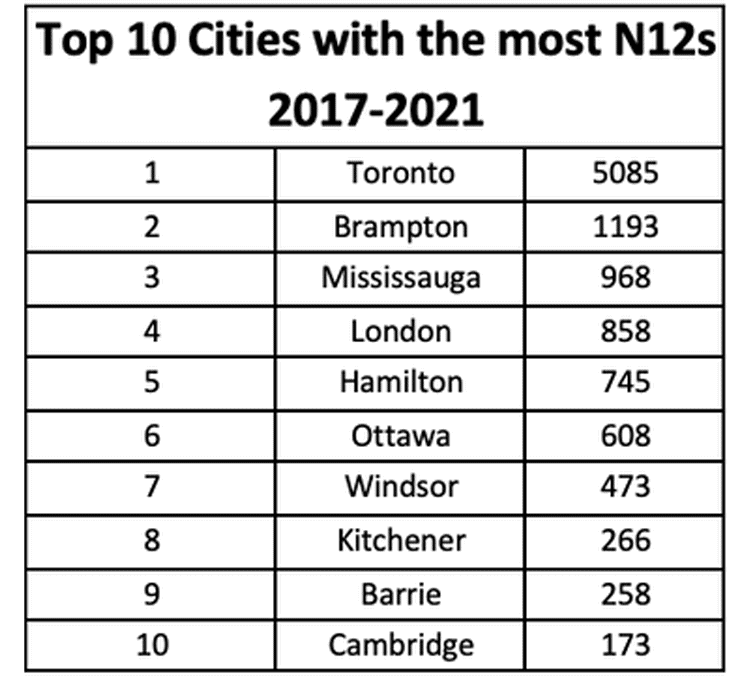

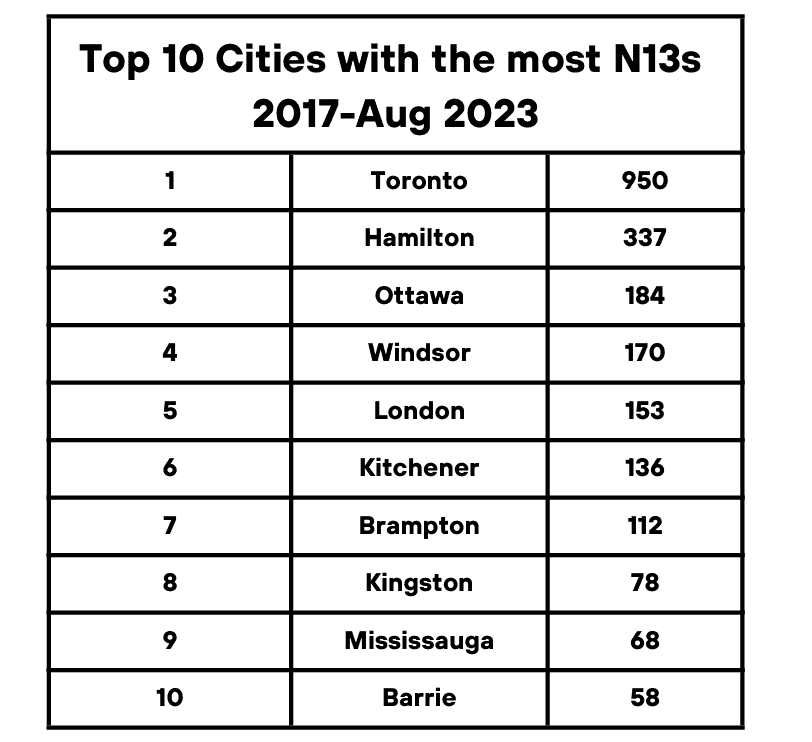

The Ontario Renoviction Report, which contains data from the Landlord and Tenant Board, indicates that N12 and N13 eviction notices are being issued more often in Ontario, particularly in Toronto, Mississauga, Brampton, Hamilton, London, Ottawa, Windsor, Kitchener, Barrie, Kingston and Cambridge.

An N12 notice is issued when a landlord decides that they or a family member intends to occupy the tenanted unit for a year or more or if the landlord sells to a buyer who wants to occupy the unit.

An N13 is issued when a landlord wishes to renovate or demolish a unit and does not want the tenant to remain in the space during construction. ACORN refers to N13 notices as “renoviction” notices, arguing that renovations often come with rent increases that tenants cannot cover, thereby forcing them out of their homes permanently.

According to the report, both notices–and particularly N12 notices–are becoming increasingly common in Brampton and Mississauga.

The report says 18,151 N12s were filed between 2017 and 2021 in Ontario–a 70 per cent increase. N13 filings are also up, with 4,067 requests filed in Ontario between 2017 and August 2023–an increase of almost 300 per cent.

Between 2017 and 2021, 1,193 N12s were issued in Brampton, making it the second most common site of such evictions after Toronto, where 5,085 notices were given.

In Mississauga, 968 notices were issued during that same time period, placing it third on the list. In Hamilton, 745 notices were issued.

Between 2017 and August 2023, 112 N13 or ‘renoviction’ notices were issued in Brampton and 68 were issued in Mississauga. The most notices were issued in Toronto (950), Hamilton (337) and Ottawa (184).

In the report, ACORN says the numbers are a ‘gross underestimate,” as most renovictions never reach the tribunal.

Brown says she knows of one tenant in her building who was asked to vacate the unit permanently so it could be renovated.

“When they took over, a lot of renovations started and one strategy [the operators] used was renoviction. One tenant was told she couldn’t move back in.”

Brown says that after tenants began receiving buy-out notices, ACORN stepped in.

“We did an action on this landlord,” an ACORN representative told insauga.com. “A lot of tenants in Nicole’s building left, thinking they had no right to return.”

Tanya Burkart, a leader with ACORN’s Peel (Brampton and Mississauga) chapter, says that although the provincial government oversees rental housing, it’s time for cities to step in to protect tenants and rental stock through workable municipal bylaws.

“There’s a gap at the provincial level in the Residential Tenancies Act. We have the right to return [to a renovated unit] but there’s no enforcement,” Burkart told insauga.com.

“Renovictions are driven by lack of vacancy control. Since there’s no regulation between tenancies, there’s an incentive to displace a tenant to make more money with a new tenant. Now we’re targeting cities because they have a better system to regulate renovictions.”

Burkart says that since towns and cities must issue permits for renovations and demolitions, they could require landlords to prove that the unit must be vacant during the upgrade process and to provide alternate accommodations while construction is ongoing.

“A lot of times, tenants don’t actually have to be displaced,” she says.

“This ensures that once the renovation is complete, the landlord must comply with the Residential Tenancies Act and allow the tenant to return to the unit at the same price. We are requesting appointments with city councillors to discuss the recommendations.”

Burkart says that cities implementing their own tenant and rental stock protection policies is not unprecedented.

Earlier this year, Hamilton’s general issues committee voted to unanimously ratify a renovation and relocation bylaw to protect vulnerable tenants in the city – the first such bylaw in Ontario. The bylaw was ratified after years of advocacy from ACORN.

The new bylaw will require landlords to apply for a licence within seven days of issuing a tenant an N13. On its website, ACORN says the license requires tenants to be provided with a tenant’s rights and entitlements package and stipulates that tenants be allowed back in their unit post-renovation at the same rent. The bylaw also requires the landlord to provide temporary accommodations or a rental top-up for the duration of the renovations.

ACORN’s report says the need to retain affordable rental stock is dire.

The report says that over 30 per cent of Ontario residents (or 1.7 million people) rent their homes–an increase of 10 per cent between 2016 and 2021. Over a quarter of renters are in “core housing need” (which means they live in substandard accommodations) and 38 per cent of renters spend more than 30 per cent of their income on housing. Fifteen per cent of renters spend more than 50 per cent of their income on rent and rental rates are rising.

According to Rentals.ca’s February 2024 rent report, the average asking rent in Ontario hit $2,456 in January 2024, with one-bedroom units costing tenants $2,239 a month and two-bedroom units costing about $2,711.

ACORN says rental rates in Toronto climbed 84 per cent between 2001 and 2021.

The report says that every time one affordable unit is built, the province loses 11 more units.

“If a family loses their home as a result of renoviction, they will have nowhere else to go,” the report says, referring more specifically to the Toronto and Ottawa markets.

“The share of units with rents costing no more than 30 per cent of a city’s lowest income household’s budget is extremely uncommon. No such units are available in Ottawa and Toronto. In other cities, the share of such units is less than 20 per cent.”

The report says rental rates increased by eight per cent in 2023, beating out the 5.6 per cent increase reported in 2022. The growth in prices is outpacing both inflation (4.7 per cent) and wage growth (five per cent).

Burkart says that without better protections for tenants, more people are at risk of homelessness, especially since many tenants are not aware of their rights.

“Any program should also include robust tenant engagement to ensure they’re aware of their rights. Offering a sum of money to leave doesn’t offer the right to return and tenants become frightened when they receive this and they take the money and leave. Given the housing supply and rental prices, it can result in precarious housing and homelessness,” she says.

Burkart says ACORN members plan to advocate for bylaws in Brampton and Mississauga.

“It’s early in the process but we’re hoping for deputations before city council. ACORN has some really great stories and tenant experiences with N12s and N13s and we successfully stopped a renoviction for an ACORN member, so it’s something we’re looking to continue,” she says.

“This bylaw will go a long way to help tenants keep the housing that they have.”

Brown says that the situation improved once ACORN got involved with tenants in her building.

“They’ve scaled back their strategies to get people to leave,” she says.

“We’ve had cleaners coming to the building more often and [management] is more receptive now when you try to contact them. They haven’t tried to get us out again since that attempt. They’re doing standard checks, fire checks, unit inspections, etc. They weren’t doing that before.”

Burkart says that overall, she’s optimistic–especially since Brampton is moving (albeit with complications) to institute a landlord licensing program.

“It’s not an easy battle to get a renoviction bylaw passed. It has taken a lot of time in Hamilton. In Brampton, we have members speaking out and sharing stories and we are hopeful someone will hear us and champion this,” she says.

“If Hamilton can do it, we just need the political will to do this.”

INsauga's Editorial Standards and Policies