Poverty is Growing in Mississauga

Published June 1, 2016 at 1:42 am

I remember the first time I was approached by a panhandler in Mississauga. It was the summer of 2001 and I was 16-years-old. I was stepping out of my father’s new-ish car in a parking lot in the Eglinton and Hurontario area when a wired older gentleman approached our group on a bicycle. He circled us — casually, not quite menacingly. I thought he was going to ask for directions.

“Hey, people with the new car. Do you have some McDollars so I can go and buy myself a McSomething?”

Hand to God, that’s what he said.

We said nothing.

Why, we all thought — silently and to ourselves — were we being approached for loose change in the suburbs? Nothing like that had ever happened before. That was a Toronto thing.

The man was adamant that we could spare some change for a burger if we could spare even bigger bucks for a glossy new ride. My father gave him some change and he thanked us and left.

We dismissed it as a bizarre one-off and we weren’t necessarily wrong to do so. Since that warm summer day in the early ‘aughts, I have been approached by less than 5 panhandlers in Mississauga. It happens so infrequently that I remember every incident perfectly (Starbucks at Dundas and the 403 in 2013 and Shoppers in the Grand Park plaza back in January, etc.).

What I’ve learned from my very occasional run-ins with loose change-seekers is that my experience isn’t unique. While extreme poverty (and even homelessness) exists in Mississauga (and the Peel region in general), it’s hidden.

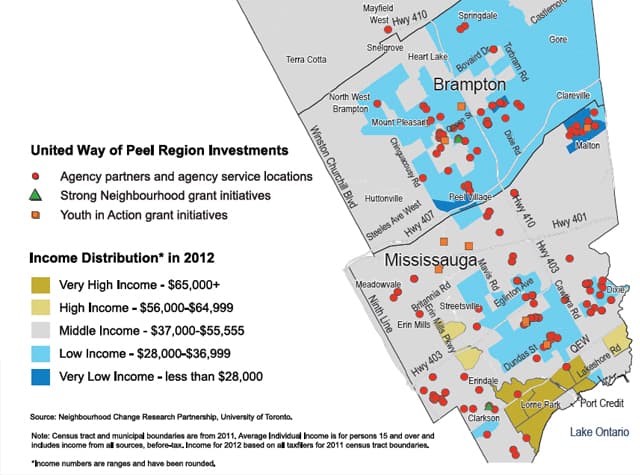

“The broader 905 is relatively new compared to Toronto and there are more mixed-income neighbourhoods and no ghettos per se,” says Carol Kotacka, vice-president, stakeholder relations and public affairs with the United Way of Peel Region. “There are low-income areas across the street from high-income ones. Roche Court is close to Sherwood Forest, for example. Poverty is hidden, but you’ll see three or four families living in one home. Some people are living in their cars. Poverty is stigmatized and it’s rare for people to admit financial trouble.”

While escalating housing prices have dominated broader financial discussions for some time, we’re finally seeing all levels of government affirm that life — not just housing, although that’s a monumental issue — is becoming less and less affordable for huge swaths of people. Mississauga city council is currently debating how to best solve its mounting affordable housing crisis because “affordable housing” is no longer just a PC catchall term for “subsidized housing.”

Now, middle-income professionals who work as clerks and social workers struggle to afford adequate housing in the city. While most people are not living on park benches, far too many people spend well over 30 per cent of their income on housing. Houses are expensive and rental rates are not, in many cases, much better.

The numbers are troubling.

According to a recent report, 74,575 Mississauga households fall within the low income bracket, bringing in less than $55,500 a year. As for middle-income households, there are currently 67,480 households that bring in $55,000 to $100,000 a year.

Thirty-nine per cent (or 92,530) households house higher-income earners who net over $100,000 a year. While it looks like the city is still home to a decent amount of higher-income households, the numbers speak of a disturbing trend — the shrinking of the middle class and the growth of individuals and families who, despite working full-time hours in professional occupations, cannot make ends meet in the city they want to call home.

For lower-income earners, an affordable house should cost $221,000 or less to own or $1,390 or less to rent. For a household with a more moderate income, an affordable home would cost $398,000 or less to own or $2,500 or less to rent. According to the report, housing affordability is an issue for one in three Mississauga households.

For one in eight households, affordability issues are serious, with over half their income going to housing costs. Some households — one in twelve — spend over 70 per cent of their take home pay on housing costs. For renters, the situation can be dire. The report notes that a whopping 42.5 per cent of tenants spend more than a third of their income on housing costs. A full 20.4 per cent spend over half.

Housing is an issue for people and families with moderate incomes — so imagine what an issue it is for people who struggle with, say, addiction or mental health challenges on top of financial ones.

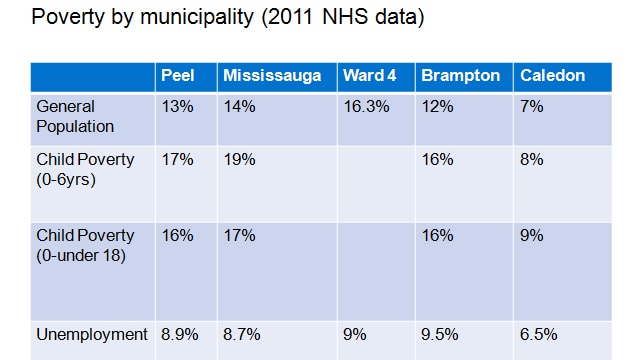

According to a recent United Way report, poverty affects 17 per cent of people and families in Peel (so in Mississauga, Brampton and Caledon, not just Mississauga). The report notes that, on any given day, over 222,000 people experience poverty and struggle to afford housing.

“Peel has over one million people and 700,000 in Mississauga alone,” says Kotacka. “Neighbourhoods struggling with poverty include Malton, Cooksville, Mavis and Eglinton and even Port Credit. The biggest challenge is creating awareness of the issue. In Mississauga, child poverty is higher than the provincial and national averages. Nineteen per cent of children aged 0-6 are living in poverty.”

According to United Way’s report, the organization’s Our Place Peel youth shelter helped 247 young people last year. While that’s certainly a good thing, the shelter had to turn away 457 youths due to lack of emergency beds.

“Mississauga has a higher child poverty rate than Brampton. It’s an affluent city, but we have one youth shelter that had to turn down over 450 people last year. Since that time, we’ve made progress creating more capacity,” she says.

As for why Mississauga has a higher-than-average youth poverty rate, Kotacka says there are a few reasons.

“It’s a growing urban center with the usual social issues,” she says. “There are [financial] challenges for newcomers, seniors, young people, minorities and single mothers. These people tend to be paid less and this drives the cycle of poverty. Also, many people have built middle-class lifestyles on manufacturing jobs and the downturn in that industry has hurt people. A lot of people are also precariously employed, working multiple part-time jobs or contract positions. Wages are stagnant and food and rent are more expensive.”

Mental illness and addiction also push people into poverty and, at this point, Peel does not yet have all the necessary resources to reach out to and treat people fighting drug and alcohol dependencies and disease.

“Peel is lacking social services,” Kotacka says. “Funding for these programs has not kept pace with population growth.”

Poverty also disproportionately affects women, seniors, ethnic minorities and people who are struggling with physical illnesses or disabilities (or caring for others who are).

“There’s a gender wage gap and a lot of seniors live on a fixed income,” she says. “Also, illness of any kind impacts your ability to earn.”

According to United Way’s report, the unemployment rate for black youth in Peel is 30 per cent — 10 per cent higher than the general youth unemployment rate. On average, black workers earn about 76 cents for every dollar a white worker makes. The report notes that young black people report feeling “unwanted, devalued and socially isolated.”

“I think poverty has stigma everywhere,” she says. “But it’s especially hidden in the region of Peel. One third of people are one paycheck away from financial crisis.”

If you would like to get involved in raising awareness and combating poverty in Peel, you can learn more and donate here.

If you are struggling with poverty (or addiction, mental illness or abuse), you can reach out to United Way by calling 211. If you’re a Peel resident, dialing this number will ensure you are connected to the appropriate service. You can also access 211 online. If you are a Caledon resident who cannot directly access 211, please dial 1-866-573-0088.

Help is available if you need it.

INsauga's Editorial Standards and Policies