Frustration Expressed at Anti-Racism Meeting in Mississauga

Published September 28, 2016 at 3:08 pm

With racism being top of mind for many, it’s fitting and appropriate that the province has scheduled a string of consultations as part of its Anti-Racism Directorate.

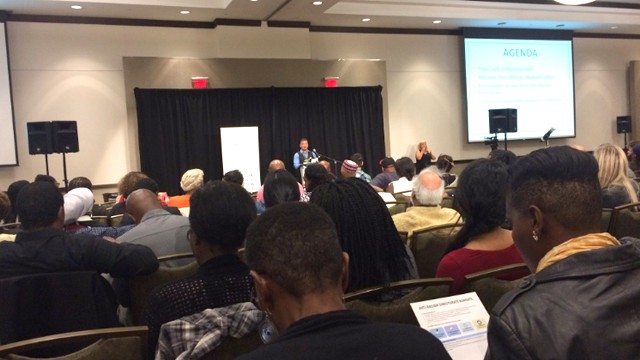

Created in February 2016, the directorate was designed to, ideally, prevent and address systemic (spread throughout a system) racism in the province. Last night, Michael Coteau, Ontario’s Minister of Child and Youth Services hosted — along with Attorney General Yasir Naqvi and moderator and current YWCA CEO Paulette Senior — a meeting at Mississauga’s International Centre.

The subject was, of course, systemic racism in the province and how to address it. Although there are people who will deny that culturally ingrained racism exists, the ministers behind the directorate are firm in their resolve to draw attention to the troublingly high numbers of black and indigenous people in the child welfare and justice systems, continued racism against indigenous people and attacks on Muslim-Canadians and their places of worship.

The directorate aims to decrease racism in government and its institutions, increase awareness and understanding of systemic racism, promote fair practices and policies that will lead to racial equality and collaborate with the community, businesses, government and the Ontario Human Rights Commission to achieve that equality.

The objectives are clear and they are undoubtedly positive. All that said, attendees at the powerful and emotional meeting almost all said the same thing — that they’re tired of meetings and consultations and want to see action.

Some key issues that arose during the meeting were racial profiling by Peel police, lack of racial diversity in government and its institutions (namely the justice, education and child welfare systems), negligence of the black community, inaccessibility of directorate meeting places, lack of policy makers and powerful figures in attendance and the government’s frustrating inability to legislate fairness and equality.

Coteau was careful to acknowledge attendees’ frustration, but insisted that policies do take time to materialize. He also said the government is currently working to find a way to make the Special Investigations Unit (the body that investigates police when a civilian is hurt, sexually assaulted or killed during an interaction with officers) more transparent.

“We’re making the province a leader when it comes to building inclusive communities. All of us need to have the same opportunities to succeed and a lot needs to be dealt with – Islamophobia, anti-black racism and anti-indigenous racism. This directorate is going to play an important role,” he said.

Coteau touched on the thorny issue of race-based data collection and everyone’s reticence to implement it (even when it might help pinpoint and therefore solve problems).

“At the Toronto District School Board, we passed a motion to collect race-based data. We started to notice things, like how we were allocating resources and that started to reveal what the system was all about [and what schools were getting more attention]. We could see that 40 per cent of black student were not graduating. We need to focus more attention on kids from that community and be accountable for what’s happening,” he said.

After several speeches about the necessity of the project and the meaningful work it will hopefully do to ensure racism is corrected and quashed at all levels of society, Senior — the night’s moderator — took to the stage to tell people to come forward.

“Tonight is about hearing from you,” she said before posing a list of questions. “What institutions have problems with racism? Should the government collect race-based data? How can the government help people understand systemic racism? How should the government work with marginalized communities to prevent and fight racism? How will the program look 10 years from now?”

As the night wore on, the speeches fluctuated in their tone (but not quite so often in their content). Some people were angry that their communities were consistently marginalized; others held back tears as they talked about their children being denied opportunities.

The first speaker began his talk by asking what the province was going to do to help the Somali community and his impassioned plea set the tone for the night.

“I’m a father,” he began. “Even though we can’t separate Somali [youth] from black youth, Somali youths suffer a lot. So many die in gun violence on Dixon Road [just northeast of Mississauga]. This is because of racism. They live in an area deprived of good schooling and opportunities. This is an epidemic for the Somali community, for the Canadian community.”

Lucy Hutchinson from Malton Neighbourhood Services spoke about the neglect of the Malton region and how community organizers aren’t empowered to bring positive change to the neighbourhood.

“Look at the agencies operating in Malton where the employment isn’t high and the economy isn’t great. Our agencies are struggling. They’re underfunded and cannot function. How on earth can people work with this? Our young people need to be employed most of our black kids, very educated, are unemployed and they get frustrated and frustrated young people are hot and bothered [and they act out] and we just build larger prisons for them.”

A social worker named Michelle (she declined to give her surname), pointed out that there’s disconnect between the people who need assistance and those tasked with helping them.

“In terms of policy research and evaluation, there’s disconnect between people involved in systems and people who run them and there isn’t enough dialogue. People affected, like indigenous people, need a greater seat at the table. We need to see training for educators. I’m a mother of two biracial children and they see how they’re treated differently from non-racialized children.”

Michelle also said that the turnout at the Mississauga meeting was disappointing and that, if youth can’t access consultation spaces, how can they know that people are concerned about them?

“In Toronto, the meeting was so overflowing. The people who need to be here, they don’t have access. This was not the place for this meeting. We don’t teach our young people that their lives matter because they turn to drugs and gun and violence. How many young black people have been shot or stabbed? How many indigenous people are missing or murdered? How do we tell them that their lives matter?”

Hammering home the salient point that race-based issues are not addressed in meaningful ways, Roger Love, legal counsel at the Human Rights Legal Support Centre, said that consistent problems with race-based disparities in the legal system are frustrating to see over and over again.

“We see problems you need to pay attention to. Look at the volume of race-based cases. It’s disheartening and our staff works hard to achieve things we shouldn’t have to fight for. We deal with cases involving police, racial profiling, incarceration and other [legal] issues that burden the black and indigenous communities. We deal with issues in the education system. Why, in 2016, do people still have to file human rights complaints because someone won’t rent them an apartment?”

Other speakers said the issue is very much a David and Goliath one — it’s difficult to prove you’re a victim of systemic racism if the system you’re fighting against is more powerful and possesses more resources. Others said that the problem isn’t always people or institutions being overtly or purposely discriminatory, it’s about them never taking the initiative to fix problems.

“Are the police here? Are Region of Peel leaders here? They should come to us, why do we always have to go to them?” asked one particularly impassioned speaker. “I want the minister to write a letter to every institution in Peel asking why they weren’t here.”

Another attendee, Mississauga-born former professional soccer player Rick Titus, also said that the issue with the meeting was that people were, as usual, preaching to the choir.

“These people are just speaking to each other, not the people who need to make these changes happen. We can do this and it’s not going to change anything. We can have data for the next 20 years, but it won’t change anything. My daughter will still go to schools where the only teachers are white ladies. Every night, I look at the news and men that look like me are shot in the street in America. I don’t see black men or women in office on a federal level. How is that affecting our children? I couch young men who don’t love themselves and don’t know anything about life. None of them are here, they can’t find their way here.”

While some speakers actually disagreed that the location was inappropriate (it was in Malton, after all), almost everyone agreed that subtle, intrinsic racism has affected them in education, the workforce and society overall. Speakers said that they were more likely to be distrusted by teachers, bullied by peers, passed over for jobs and promotions, targeted by police and ignored by government organizations and related institutions. Many asked that legislation be implemented to increase the presence of people of colour in government, policing, social work and education. Many also asked that the government collect race-based data so that persistent challenges within minority communities can be targeted and addressed in an honest and meaningful way.

Although the conversation was a difficult (and a sad and angry one), it was respectful and reiterated what we all know and often ignore — everyone must work to address and eliminate discrimination.

INsauga's Editorial Standards and Policies